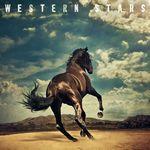

Bruce Springsteen Western Stars

(Columbia)

Every so often, Bruce Springsteen deviates from his rock-oriented records to pursue mellow, quieter projects. He's been consistent at it, usually followed by more vigorous statements—2005's acoustic-heavy Devils and Dust followed 2002's bootstrapping The Rising, 1995's lean, story-driven The Ghost of Tom Joad followed the smooth, album-oriented pop-rock of 1992's Human Touch. The Jersey rock legend repeats this cycle every decade, revealing aspects of American life through human stories that read like folklore and legend. On his 18th album, Western Stars, "The Boss" goes back to a sound that, curiously, wouldn't have sounded out of place in the early seventies—right before his debut album Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. And yet, it's the kind of ambitious statement that sounds fitting after a fifty-year career culmination.

In many ways, the sleek, California sound of Western Stars is a stark contrast from the stripped-down approach of Tom Joad or Nebraska. The framework of these songs is simple, even when they're adorned with opulent strings, stimulating horns, and heavenly piano chords. Tuscon Train and There Goes My Miracle are about life's eternal search, where the anonymous characters he details amble through life with the promise of better things to come. Springsteen is also at his most self-aware, like in The Wayfarer, conducting pronounced instrumental touches in between every single verse: "It's the same old cliché, a wanderer on his way, slippin' from town to town." At this rate, it's safe to say that he's earned the right to embrace such banalities—especially when they feel so lived-in.

It's especially discernible how Springsteen freely borrows from the sometimes breathtaking, something slushy balladry of sixties-seventies singer-songwriters. Hello Sunshine is undeniably beautiful, a galloping country tune about embracing one's sadness, but not getting too enamored with that feeling—and it couldn't sound like a more suitable tribute to Harry Nilsson's version of Fred Neil's Everybody's Talkin. Drive Fast (The Stuntman) is equally contemplative, telling the story of an everyday daredevil who's battling through his present, both physical and emotional—it gets to reach its climax with a swelling orchestra of Burt Bacharach proportions. It may seem like a retrograde idea, to embody a foregone period with such distinction, but Springsteen's narrative choices feel timeless in how they address contemporary concerns, too.

Rather than follow a linear concept, Springsteen creates different vignettes that conjure the transient up and downs of forging your path. The mid-tempo Sundown, the closest here to a rock song, is about a drifter who's got a lot of miles to go before he's able to greet his love again. But there's also a lot of joy to be had in driving cross country, like in Sleepy Joe's Café, where he stumbles upon a little utopia in the middle of nowhere—a laidback retreat where the long-haul truckers and the Harley bikers live like it's always Friday night. It's also one of the few times where Springsteen settles into a Key West state of mind, embracing a jam-band feel with his toes dipped in a sandy beach. Though Springsteen occasionally indulges in cutesy, roots rock tropes—the recent Wrecking Ball's sure got a lot of those—it feels at odds with the album's otherwise solemn, sophisticated mood.

There's something familiar about Springsteen's existential plight, a topic he's weathered time and time again with a different musical emphasis. He's often direct and political, but this time, his subjects are roving and circuitous—uncertain about their predicted fate. As a woozy patron stumbles his way as he thinks about a distant lover during the melancholic, folk-led closer Moonlight Motel, he turns our attention to these open-ended conclusions. In Western Stars, the old adage about finding meaning through the journey couldn't feel truer. And that's an idea that Springsteen can relate to—leaving a little bit of yourself in a landscape that feels immortal.

16 June, 2019 - 23:24 — Juan Edgardo Rodriguez