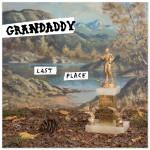

Grandaddy Last Place

(30th Century Records)

An established band’s return after a long absence is usually done with rational cause. In the case of Grandaddy, the sudden return after a period of dormancy wasn’t exactly either a desperate reappraisal or a forced necessity. It just felt right. No acrimonious breakups here. In fact, the actual reason behind those ten years of silence is as dull as it is sensible: even if frontman Jason Lytle has never felt completely at ease with the challenges of collaboration (he did write two solo records during this time, after all), it was also about controlling, and eventually putting a stop to, gradual success before it becomes a problem. One can detect self-sabotage as a defense mechanism here, seeing as holding on to the Grandaddy name meant bearing a responsibility to keep the project afloat for the rest of its band members.

Coming back from Montana after having a need to “reconnect with the natural world”, Lytle has returned to his hometown of Modesto, California with a renewed sense of purpose. Normally it may seem as a preposterous excuse to escape reality, but in Lytle it makes perfect sense considering his typically unanchored lyrical focus always suggested a troubled persona who’s overly sensitive about the struggles of unfulfilled potential. A crippling anxiety has followed his work for the entirety of Grandaddy’s prolific decade, even if he’s wrangled with these feelings by putting the focus on bizarre conceptual themes, muttered in a crestfallen tone, despite not being quite sure what they’re about. Lytle addresses sadness with a sweeping grandiosity, where the stories he conjures are both sides amusingly satirical and deceptively foolish.

On Last Place, Lytle isn’t hiding his persona behind androids or cats. It’s the closest he’s come to writing about himself in a more direct manner since 2003’s Sumday, where Lyle gave his usual sonic trinkets a more subtle accent to underline his iridescent mid-tempo melodies. At times, the similarities are striking: on The Last Part, a downcast Lytle recounts in internal monologue about an apparent domestic dissolution ("This is the part that shouldn’t had been hard / Where there is peace / You will not find me”). The calamitous The Boat is in the Barn is an antecedent to the events that unfold in The Past Part, where Lytle imagines how his significant other is presumably, at least how he interprets it, enjoying herself as she deletes memories of them on her phone. If it isn’t any clearer, the classically-informed instrumental Oh She Deleter :( features one of Lytle’s most splendid piano compositions, a form of writing he’s been quietly tucking into each of his albums as far as 1997’s Under the Western Freeway.

Other than Grandaddy’s spacey flights of fancy, a large majority of Last Place also brings back the fuzzy power chords of past records. The band is categorically known for their disciplined uniformity, an approach that gives the band more room to inject more personality into their straightforward rhythm section; seeing as the indie rock landscape has also considerably changed, it’s actually a welcome throwback that’s aged well. The Way We Won’t sounds like it could’ve been conceived twenty years ago, sure, but it’s genuinely rare to hear them brew such a catchy chorus, and with such wide-eyed aplomb to boot. The stately I Don’t Wanna Live Here Anymore is hook-heavy power pop with a heart, and though the underlying message is as sad as it’s ever been, it also has the potential to thrill those who feel as dispirited as he does with a simple sing-a-long chorus.

Last Place markedly separates itself from Lytle’s concerns about technology and how it deprives our human qualities. It’s not just a concern anymore. It’s a reality, and though he vaguely alludes to how these advancements cause a disconnect it directly puts the focus on its characters (or himself?) to provide a stronger emotional pull. His sense of humor is still there: the slight gag about recurring character Jed in Jed the 4th ("And he don’t come around no more / You know it’s all a metaphor") caused a pleasant chuckle. But never has he made more sense about how both the human and the artificial coalesce in the epic A Lost Machine, where he simply states that we’ve completely succumbed to chemical engineering ("Everything about us is a lost machine") as it builds into a majestic ballad. Lytle is aware that any technological advancements haven't made us any happier, and now he’s sure that we’ll never return to a more natural state of being.

But the actual event that creates a real maelstrom, seething within all this technological wreckage, in Lytle’s songs is a very human one: love. And even if it ultimately doesn’t end well, there’s no more human feeling than giving life’s most selfless and defenseless task a fair shot. [Believe the Hype]

27 February, 2017 - 04:06 — Juan Edgardo Rodriguez