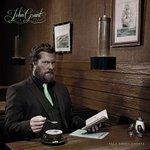

John Grant Pale Green Ghosts

(Bella Union)

It’s perhaps an interesting quirk of the cross-over success of Weekend that one of the few films to break out of the gay ‘ghetto’ would be one that was uncharacteristically political. For all the low-key earthiness that defined the film’s camp-shirking portrayal of a same-sex love affair, there was a fair amount of discussion as to what the end-game of the equality struggle should be; if a gay lifestyle could ever be entirely compatible with an ever-more tolerant mainstream society, or if such a thing is impossible (or even desirable) thanks to the deep impact the whole process of coming to terms with one’s sexuality will have on a person (and, unfortunately, that’s just the start of it).

In a bit of a neat segue, thanks to that film’s borrowing of a couple of tracks from his solo debut, Queen of Denmark, it’s also a question that arises when listening to John Grant’s second album, Pale Green Ghosts. On the one hand, there’s so much that’s immediately appealing about the work - his verbose, witty and frequently charming lyrics that are so good at articulating ideas and feelings that although highly, even brutally, specific, feel universal, the warm bear-hug of a voice that they’re delivered in, and the accompanying clean, crisp production from GusGus’ Biggi Viera - that these songs could appeal to a wide audience on the other, though, there’s a sense that the gayness is key to the album’s success. Even looking past the gendered pronouns (which we are perhaps encouraged to do, thanks to such lyrics as ‘I watched Jane Eyre last night, and thought about which role, would work best for me’), it would be fair to say that there’s something exclusively male about the majority of the album’s tales of bitter heartbreak; the withering putdowns that are formed from a mix of cruelty and apathy (which are pretty much the same thing), or pointed lyrical references to the shapeliness of an ex’s buttocks, would perhaps be just a little bit too distasteful when addressed by one gender to another (as it is they’re still pretty uncomfortable here). Taking this notion further, it even extends into the album’s sound, as the often quite skeletal arrangements that are built around Grant’s baritone definitely skew towards the lower end of the spectrum, with the occasional sharp bursts of the higher registers of vintage synths, or skronking saxophone, or backing vocals from Sinead O’Connor (returning the favour after covering Queen of Denmark’s title track on her last album, and rather sweetly credited here as ‘Mrs. John Grant’), working as an effective shock to the system.

The involvement of Viera might have perhaps tipped fans off that Pale Green Ghosts would offer a bit of a change in style from Queen of Denmark, that the lush orchestrations provided by Midlake on that album would be sadly jettisoned here, something probably confirmed by the release of the title track as lead single, and yet, while a definite progression, it’s not as dramatic a volte-face as initially expected. As Denmark’s 70s soft-rock sound came as much from a conceptual autobiographical framework as anything – a deliberate attempt by Grant to evoke a more comfortable, innocent period in his life – the same could be said for the track’s driving electro (mixed with a little bit of Rachmanioff), which fittingly reflects his youthful escape of driving through Colorado to Boulder’s nightlife, and while this tone continues into the spiteful funk of second track Black Belt - the first of the many bitterly sardonic attacks at Grant’s ex - much of the rest reverts back to the more familiar, specifically a soft-rock balladry that ably straddles lushness and adorable awkwardness in a style that sadly went out of fashion with Gilbert O’Sullivan, or falls into a sort-of hinterland between the two where acoustic guitars rub up against slinky basslines and abrasive synths (for a frame of reference, think a less arch version of what Air were going for with 10,000 Hz Legend).

Perhaps the exception is Ernest Borgnine, which, while falling squarely on the electronica side, exudes a quiet, abstract menace that’s entirely its own. But then, considering the subject matter – Grant’s HIV positive diagnosis - it would arguably have been a standout even if it had been a straight rewrite of any of the other tracks here. It’s true to say that there have been a sizable amount of both artists who have been afflicted with the condition, and well-meaning attempts to write about it in song, but on listening it’s striking just how uniquely honest and lacking in hysteria this take on the subject is; perhaps it’s because of advances in treatment rendering it no longer the absolute death sentence that it once was, or maybe it’s because no artist with such a gift for candour has found himself in this position before (or, as South Park pointed out, it might just be that enough time’s passed that it’s now acceptable to make jokes about it).

Fortunately, for such stark autobiography, Grant is, in an industry that seems to be dominated by blank careerists, the increasingly rare type of artist whose work actively invites and rewards further investigation into his personal history. Thanks to their overlapping time structures, it’s possible to read his solo albums as two halves of a whole, and as the first record punctured Grant’s self-lacerations with optimistic accounts of his recently finding love again, the painstakingly detailed accounts of the breakdown of that same relationship here essentially rewrite the narrative of what went before, in a Blue Valentine kind of way. (This is even reflected in Pale Green Ghost’s artwork, as the candy skulls that adorn the inlay bring a rather macabre hue to the sweetshop reveries of earlier single Marz). And while the history of pop music is hardly wanting for accounts of finding or losing love, they’re rarely rendered so transparently as they are here.

Not that it’s all doom and gloom, mind you - we may be presented with a fairly extensive catalogue of Grant’s faults (not that there’s anything here to match the casual savagery of Queen of Denmark) but it’s impossible to dislike a guy who, by way of venting at his ex declares himself to be ‘The Greatest Motherfucker that you’re ever going to meet’, yet by the end of the same song is audibly losing confidence and quietly attempting to downgrade expectations. Throughout its running time, Pale Green Ghosts sees Grant ably balance a sense of humour with quietly devastating content.

The closing Glacier, for example, is as much of a gut-punch as Ernest Borgnine, if not more so. With a simple directness that could, in the wrong hands, easily fall into the category of trite, he draws on his experiences of growing up gay in a Christian household, and offers more advice (as a bonus, all beautifully harmonised with a uncharacteristically sedate O’Connor) than could be found in an infinite number of ‘It Gets Better’ videos.

To be honest, with so much emotional flip-flopping going on, Pale Green Ghosts is something of a demanding listen. Also, as it comes in at just over an hour, with most tracks stretching out to five or six minutes, it's not just the listener's emotions that it places demands on, and as a result the later indulgences on the album might not be viewed with such forgiveness. Perhaps most so, in Sensitive New Age Guy which, despite neatly being tucked away at the back of the album, does stick out by its relative opaqueness, to the extent that its inclusion seems to be a bit of a puzzle. On the other hand, it also sees Grant offer up an unexpectedly convincing impersonation of LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy, so while out of place, it’s not exactly unwelcome.

As to whether those qualities count as flaws that stop Pale Green Ghosts reaching the status of being a perfect album, or instead serve to make it all the more appealing by giving difficult subjects breathing space and perspective, will probably depend on how much effort you’re willing to put into listening to it. But then Grant’s work here aims at something much more rare than perfect – to be entirely necessary, serving to not only function as an essential outpouring for the artist, but as a well-intentioned fount of advice to the listener; serving as a reminder that no matter how bleak things seem there are still reasons to laugh, hope and be grateful, as the endearing humility of It Doesn’t Matter to Him’s opening thoughts, ‘If I think about it, I am successful as it were, I get to sing for lovely people, all over this lovely world’, pinpoints. Who would’ve thought that a break-up album could, amongst all the bitterness and recrimination, leave such an over-abiding sense of warmth and generosity?