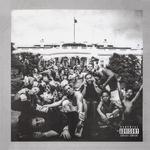

Kendrick Lamar To Pimp A Butterfly

(Interscope)

“Your horoscope is a Gemini, two sides/So you better cop everything two times.” In an album boiling over with thesis statements, this one, from the final verse of opening track Wesley’s Theory, is particularly constructive. To Pimp A Butterfly is an album about contradictions—the contradictions of fame and artistry, of escape and home, of Kendrick Lamar himself, and the schizophrenic condition that W.E.B. Du Bois’ termed “double consciousness” in The Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois’ term refers to how black identity has split into multiple facets as a result of the disparity between African heritage and enslaved upbringing in White America. That double consciousness, that two-sided Gemini, takes the form of u and i, as two dichotomous tracks are called, and challenged, reconciled, historicized, and complicated through the album’s self-conscious positioning and Kendrick’s lyrics, both of which seem to be fighting themselves on every level.

On the note of the former, around the same time To Pimp A Butterfly “leaked,” Kendrick tweeted that the previous day was a “Special Day,” a reference to the 20th anniversary of Tupac’s Me Against The World. That album, released while Tupac was in jail, showcased the rapper’s other side. Tupac, like Kendrick, was a man of contradictions. He had “THUG LIFE” tattooed across his belly but claimed that he wasn’t a gangster; it meant “The Hate You Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody.” He lamented the pointless deaths of many friends on Me Against The World’s“So Many Tears.” He helped pioneer “gangsta rap” and got away with shooting cops but wrote poetry, studied theater, and had a fondndess for Shakespeare. To Pimp A Butterfly, which explicitly addresses itself to Tupac in its final minutes, is very much a response to Me Against The World. By the same token, appearances by Parliament/Funkadelic mastermind George Clinton (on aforementioned Wesley’s Theory) and sampling of James Brown (on King Kunta), Ahmad (same), Ron Isley (on i) and Fela Kuti (on Mortal Man), other nods, and the versatile work of the numerous producers and writers self-consciously place Kendrick within a lineage of “black music.” Still, To Pimp A Butterfly was produced largely from the ground up—samples are relatively few—making Kendrick’s album closer to D’Angelo’s Black Messiah than to Public Enemy, whom the album sometimes recalls in its more confrontational lyrics.

And it’s precisely those confrontational lyrics that make To Pimp A Butterfly an unforgettable album. To say that To Pimp A Butterfly is not like good kid, m.A.A.d city is an understatement. good kid was billed as “a short film by Kendrick Lamar,” and the way its lyrics painted a picture for listeners to look at made it an appropriate billing. Listeners were never implicated or addressed or made to feel threatened as Kendrick showed off Compton. To Pimp A Butterfly is not safe. Accordingly, there is no Backseat Freestyle on thisalbum—or at least, not much of it. The raps on that song exemplified everything that make Kendrick a superb craftsman; the multisyllabic rhymes, both end and internal; placing syllables that we don’t accent in normal speech on the beat to give them emphasis; use of elision, in which he alters the chorus to set up a series of third verse rhymes; his ability to pack so many different, often complex rhythms into the song, even a single verse. It showcased that Kendrick is a very idiosyncratic rapper, but even that idiosyncrasy came with a clearly defined relation to the beat. It’s a distinctly rhythmic rap, which is why you can sing along to it, and it’s a showcase for the method that Kendrick practiced throughout the album.

Those aren’t completely gone on To Pimp A Butterfly, but the King Kunta’s on the album (of which more later) feel more like exceptions than rules. Take, for example, the final verse of the stunning u, where Kendrick raps, “I know your secrets, nigga/Mood swings is frequent, nigga/I know depression is restin' on your heart for two reasons, nigga/I know you and a couple block boys ain't been speakin', nigga/Y'all damn near beefin', I seen it and you're the reason, nigga.” There is an internal rhyme on the third line that fits outside the scheme, “depression is restin,’” and another with the word “beefin,’” but that aside, it is a series of end rhymes, followed by an intense, hateful utterance of the word “nigga,” one that almost brings out the hard “r” sound identified with racist utterances rather than rap music. But these rhymes are hard to detect when listening because Kendrick, perhaps because he is imitating the drunken, hateful, self-doubting voice in his head, speaks his lines rather than raps them. The beginnings and ends of his lines have no relation to the drumbeat that ostensibly marks beats and measures. It’s the pause and pronunciation of “nigga” that unites these lines and shift emphasis off the rhyme to the epithet, spoken harshly and hatefully, as if the white voices and institutions that trouble Kendrick throughout the album have forced him to internalize a hateful, racist label for himself. In m.A.A.d City Kendrick described uncomfortable realities, but Kendrick’s surefire rhythm reminded us that we were always listening to a rap song. In u, his cadences, the drunken slurring of words, the sounds of hiccups and bottles smashing, create a listening experience of genuine unpleasantness and physicality.

Looking at u, we must thereafter turn to i. Here, Kendrick preaches once again to those thousands alluded to so disdainfully in u. The song, originally criticized as corny, is here presented in a live recording, complete with calls to “come to the front” that give the song a physicality different from that of u. i is Kendrick fighting back against the demon from u, a self-loving response to that song’s self-loathing. The song itself is a manically energetic anthem elevated by back-up vocals, and some remarkable sampling of the Isley Brothers’ That Lady, and of course Kendrick’s confident rhythm—a brief foray into the mode in which we first learned to love him, and one diametrically opposed to the cadences of u’s final verse. Indeed, while u ended with repetitions of “nigga” that reaffirm the word’s vulgarity and pejorative contexts, i ends with a speech reclaiming it, tracing its origin back to the word “Negus,” which denotes a king in Ethiopia. With i, Kendrick turns the institutional hate that overpowered him on u into a positive part of his identity, reclaiming the word as his own. “Kendrick Lamar, by far realest Negus alive” he declares at the end of the song.

Looking at u and i first appears to be a useful synecdoche for To Pimp A Butterfly, two songs that encapsulate the journey from hate to love and rejection to acceptance. But this is an album almost boiling over with paradox and contradiction. The u/i dichotomy is a false one, and taking it for granted erases the far more complicated and ambiguous politics of the album. Each verse of The Blacker The Berry reminds the listener that the “double consciousness” is not merely two voices that can be separated, as those two songs do, but rather a complex network of signifiers and voices. In it, Kendrick tears into white institutions in scintillating verse after scintillating verse, almost turning hateful stereotypes into empowerment anthems—“My hair is nappy, my dick is big, my nose is round and wide.” He goes on, slam-rapping “You hate me don't you?/You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture/You're fuckin' evil I want you to recognize that I'm a proud monkey/You vandalize my perception but can't take style from me” over a smooth, keys-based beat. At the end, however, the internal contradictions manifest externally: “why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street?/When gang banging make me kill a nigga blacker than me?/Hypocrite!”

Much has been made of this ending. Is Kendrick suggesting that the Rudy Giuliani statistic, “93% of Blacks in America [who] are killed [are killed] by other Blacks,” has merit? The statistic is true, but because murder is more likely in impoverished neighborhoods and cities, and institutional racism has kept Blacks hyper-segregated and impoverished. Giuliani’s sentiment, reflected in the end of The Blacker The Berry, isespecially troubling in light of Kendrick’s recent quote about Ferguson. Speaking to Billboard, Kendrick said “What happened to [Michael] Brown should’ve never happened. Never. But when we don't have respect for ourselves, how do we expect them to respect us?” It is easy for someone pontificating from on high to suggest that Kendrick doesn’t “get it,” but the explanation that cuts to the heart of To Pimp A Butterfly is that Kendrick is angry at himself for playing into a system that pits Blacks against other Blacks rather than somehow opting out of it. It’s why in Complexion (A Zulu Love) Kendrick uses an elongated slave metaphor in a verse that ends with “Let the Willie Lynch theory reverse a million times.” Again, some see it fit to take Kendrick to task on the grounds that the Willie Lynch letter may be a hoax, but the content—that slaves can be set against one another by exploiting their differences—is almost certainly not, and that logic persists in Black communities today. It is this exploitative maneuver that Kendrick (or perhaps his character) has fallen for in The Blacker The Berry. Comparatively, Kendrick clearly “gets it” when, in his spoken word outro of Mortal Man, a verse that he builds up line by line over the course of the album, he says “Just because you wore a different gang color than mine/Doesn’t mean I can’t respect you as a black man…if I respect you, we unify and stop the enemy from killing us.” “If Pirus and Crips all got along…,” we might recall Kendrick saying m.A.A.d city, but when you have the government contributing to the drugs and gun epidemic, as Kendrick draws on in Flying Lotus produced-opener Wesley’s Theory (the first of a handful of song of the year contenders), gangs aren’t going to get along.

This repeated equation of slavery (a form of racism that differs from today’s institutional racism only in its visibility) and its lingering impact on the Black psyche is a recurring theme on To Pimp A Butterfly. Kendrick goes on in Wesley’s Theory to invoke reparations for slaves at the start of the second verse, rapping “What you want you? A house or a car? Forty acres and a mule? A piano? A guitar?” and “wear those gators/cliché and say ‘fuck your haters.’” These lyrics show the same perceptiveness that Kanye West did on New Slaves, alluding to the way “Uncle Sam” tricks Blacks into a consumerist lifestyle while making entertainment their only path out of the ghetto to the house and the car. He invokes the need for reparations again on the very next song and yet again on Alright. On the latter song, he repeats Wesley’s Theory’s verse verbatim for four lines, but swaps out “Uncle Sam” with “Lucy.” “Lucy” is set in opposition to “Sherane,” who listeners will remember from good kid, m.A.A.d city, although For Sale? (Interlude) makes it clear that “Lucy” is short for Lucifer. Still, the personification of the devil as a woman presents a problem on the album, particularly following the sympathetic portrayal of a prostitute on good kid, m.A.A.d city’s Sing About Me.

It is not only stance on To Pimp A Butterfly that is troublesome. Mortal Man sees Kendrick challenge his fans to stay by him if a government conspiracy finds him in hot water, but he draws on Michael Jackson as a comparison, declaring “he gave us Billie Jean, you say he touched those kids?” It’s certainly the least justifiable lyric on the entire album, and that it comes on a closing track in which Kendrick puts himself in lineage with Martin Luther King, Jr and Nelson Mandela is even worse.

In any case, Kendrick’s double consciousness, invaded by “Lucy,” is made personal through the narrative of his getting famous, leaving Compton, and eventually returning home. The first verse of the opener tells us outright, “When I get signed, homie I’mma act a fool” and then lists a number of materialistic indulgences. In King Kunta, the most remarkable song on a most remarkable album, Kendrick portrays himself as a man atop the rap game and the music seems to shape itself around his speech rather than the other way around. The slave-metaphor of choice is a pop-culture one, Kunta Kinte of the TV show Roots running away while “everybody wants to cut the legs off him.” The journey Kendrick takes from calmly declaring “I’m mad, but I ain’t stressed” to casually reminding us of his superiority through his lyrics, rhythm, and production while suggesting others use ghost writers is astonishing. To make matters worse (for Kendrick’s addressees, that is), as soon as Kendrick makes it clear that the throne is his—a feat that takes only about half the song to establish—he brushes off his own effort, as if he abandoned it halfway through. “I was gonna kill a couple rappers but they did it to themselves/everybody’s suicidal they don’t even need my help.” In addition to establishing Kendrick as the runaway favorite for the throne, the lyrics emphasize the deeply personal journey of the album.

The narrative continues, taking sadistic turns, seeing Kendrick punish himself for his absence from home on u and being tempted by “the evils of Lucy,” which disappear when he returns home as per the lines added to the album’s growing verse on For Sale? Thus, the first interlude signifies the transition into a materialistic hedonism while the second ushers in the phase of the album in which Kendrick overcomes it and is best demonstrated in the electrifying, fade-out verse that closes Momma. But just as the album seems to be returning to relatively didactic territory, it becomes apparent that coming home does not necessarily mean returning to Compton. Complexion (A Zulu Love) and The Blacker the Berry both refer to Zulu and Mortal Man references Kendrick’s trip to South Africa. “Momma” is also the motherland, and the importance of returning home, not forgetting where you came from in spite of success, imperceptibly merges the personal with a Black Nationalist awareness of one’s roots. The change is not an erasure of King Kunta, but rather an illustration of the way that, for Kendrick, the personal is intrinsically linked to larger, overarching concerns.

While this confrontational mix of personal and political only further strengthens Public Enemy comparisons, Kendrick is not without his contemporaneous equals. Janelle Monáe is now five suites (an EP and two LPs) into an Afrofuturist epic that acknowledges intersectionality in its social justice allegory. The “genius full of contradictions” album, meanwhile, was done by Kanye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. But To Pimp A Butterfly contains elements of all three artists, and its self-aware and probing nature highlights that the album’s flaws, ideological and otherwise, are being worked through by the artist.

How far can To Pimp A Butterfly’s self-consciousness go in aestheticizing its flaws? Can we excuse the Michael Jackson remark on account of another of the song’s lyrics, “as I lead this army, make room for mistakes and depression”? What to do with the bizarre metaphor of These Walls, equating sex with prison, which arguably adds little to the narrative? How Much A Dollar Cost?, in which a homeless person for whom Kendrick neglects to spare change reveals himself to be God, might be too blunt in its message. That To Pimp A Butterfly forces difficult questions both sociopolitical and aesthetic is testament to its brilliance. It is an album that can be, even deserves to be annotated song-by-song, line-by-line.

Whether these flaws add to the album’s mystique, clarifying that this is an album fighting with itself on almost every level, or merely hinder it from perfection is up to the listener. If there is perfection here, it is in the chosen ending, where the built verse turns into a conversation-of-sorts with Tupac—an explicit nod to the importance and role of predecessors. Kendrick relates an elongated entomological metaphor that encapsulates the album’s themes and refers in name to previous songs. He concludes his parable by advocating that experiential education be used to help turn the institution against itself, but Tupac responds to Kendrick’s conclusion with silence. Kendrick must again venture alone.

6 April, 2015 - 02:35 — Forrest Cardamenis