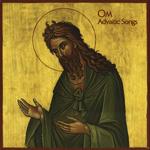

OM Advaitic Songs

(Drag City)

Defining a post-metal genre cultivated and nurtured by Eastern meditation and drug-fueled interpretations of trance-inducing rhythms, Al Cisneros and Chris Hakius, the rhythm section of the legendary doom metal band, Sleep, formed OM, which served as a stripped down continuation of Sleep’s immense sound and Sabbath worship. The duo’s expansive, audible journeys functioned through cyclical bass rhythm and a voluminous clangor of percussion, maintaining a meditative drone of instrumentation that seemed isolated as in prayer or internalized reflection. The duo’s 2006 release, Conference of the Birds, is two tracks clocking at just over 30 minutes, unifying both the powers of the entrancing loop and the prominence of distorted groove. The first time I listened to it, I was overwhelmed by its presence and immediately hooked. I’ve been a fan ever since.

Following the band’s 2007 release, Pilgrimage, Hakius left. In his place, Emil Amos, drummer for the spiritual-centric instrumental band Grails, took over percussion for OM and brought with him the overt Eastern flavor that Grails base most of their musical themes and soundscapes. The union makes perfect sense: Cisneros with his leanings toward biblical reference and penchant for spiraling bass chants and Amos having helped churn out more than a few explorative, mind-expanding musical narratives. This new partnership resulted in 2010’s God Is Good, the Grails dynamic thickening OM’s former minimalism by adding more complexity, texture and instrumentation. Cisneros, though, remained the band’s identifying factor: his propulsive low end left as OM’s most dominant and crucial device.

OM’s new album, Advaitic Songs, continues the band’s progression into Grails’ more refined otherworldliness, dialing Cisneros back in order to bring prominence to bowed instruments and woodwinds, sitar howls and hand drums. The album doesn’t just represent a musical transition, but an almost complete overhaul. Through legacy alone does Sleep remain tied to OM’s sound, the only real exception being The State of Non-Return, though the band’s usual depth of sound, (in some of the other albums, even God Is Good, OM’s percussion splays through space like the drum kit sits in the middle of some vacant temple), is notably compressed. Cisneros’ vocal drones are mostly consistent, his bass tone driving the song through its more sophisticatedly performed construct. Otherwise, Cisneros spends most of Advaitic Songs supplying the album its low end as opposed to telling the music where it’s going.

Advaitic Songs begins with Addis, female prayer sounding its intro. Cisneros is present, though incorporated into the song’s fabric. Guitar strings are plucked, stringed instruments and piano keys flare. An almost documentarian take on ritualism seems present throughout the album, the 10 minutes of Gethsemane reveling in choral glory before Amos throws down a ringing snare foundation. Cisneros, for being as low on the volume as he is, provides the track an excellent bass melody while cellist Jackie Perez Gretz (Giant Squid, Grayceon) adds grace through bowed instrumentation. The trio’s interaction works its way into a solid jam before the song’s outro, a steady fade transitions into Sinai, which builds through slow swells of sound and obscured chants.

Sinai works similarly to Gethsemane, Cisneros with a present, though not prominent or distorted, bass line, Amos clanking the ride cymbal in a steady, head-knocking rhythm. Cisneros, a bit of distortion added to his vocal, delivers his lines in sentence fragments while cello strings beautify the basics. Between Gethsemane and Sinai, the songs almost work as a medley, or at least two different perceptions with the respect to the same basic idea. Together, though, they sound fluid and necessarily entrancing.

As Addis had in its beginning, Advaitic Songs ends with a very ornate, ritualized piece of music called Haqq al-Yaqin. Hand drums and cello strings sound, vibratory percussive enhancements icily ring, a tympani sized thud announces the instrumental hook. “And the phoenix has ascended/flies upon the divine wind,” Cisneros speaks before the music is carried to fruition by dueling strings and bowed melody.

While some might consider OM’s progression to be somewhat of a kowtow or catering to Amos and his musical ideas, it’s difficult to deny that OM’s essence still communicates enlightenment or at least attempts to induce some state of internalized solace. It’s also difficult to really predict how OM would’ve continued creatively without some exposure to new possibilities. If Advaitic Songs can claim any flaw, this would be its production, which is very clean and exposes its intention for isolated sounds as forced. Next to the realized space of OM’s previous albums, which has always contributed greatly to the spiritual and meditative focus they convey, Advaitic Songs sounds flat, a detriment to the album which might otherwise be, next to their grandest, OM’s most accomplished.

24 July, 2012 - 08:28 — Sean Caldwell