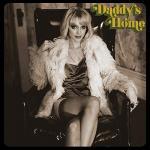

St. Vincent Daddy's Home

(Loma Vista)

Concept albums seem to take two forms. They’re either cartoonishly over-the-top (and often space themed) showstoppers—the ones fronted by superheroes or aliens or just solipsistic rappers—or they’re subtle and deeply personal narratives, a curated stroll through a snapshot of time or place.

A concept album that exists between these two worlds is an oddity, yet arguably one that St. Vincent has succeeded in creating in the past. Masseduction represented the media’s obsession with youth, beauty, and female celebrity forced to confront itself. Dramatic without being campy, poignant without being personal revealing, the record may have captured the right balance in part thanks to the clinical subject matter.

It’s intriguing critical candy, then, when a rock star known for her glamour and sleek presentation—both aesthetic and melodic—teases a new album with an illicit and much more personal twist. Daddy's Home soundtracks her father’s release from a medium-security prison for a high profile, white-collar crime, and the album welcomes him with a pastiche of the 1970’s acts he raised her on.

One look at the promotional posters would have you convinced (and a little hopeful?) that Daddy's Home would go full camp. Standing in cross-armed contrapposto in a maroon leisure suit and white platform boots, Annie Clark sports a Gena Rowlands bob and a defiant smile (and looking for the life of me like a blonde Shelley Duvall). The copy parodies vintage magazine ads from the era: “St. Vincent is back with a record of all-new songs. Warm Wurlitzers and wit, glistening guitars and grit, with sleaze and style for days. Taking you from uptown to downtown with the artist who makes you expect the unexpected. So sit back, light up, and by all means have that bourbon waiting, because DADDY’S HOME.” It’s John Cassavetes, it’s Pulp Fiction, it’s Andy Warhol. It even cheekily advertises an 8-track release. It’s practically begging for an alter ego frontwoman. Sadly, she never appears.

The backdrop is there and it’s pervasive: the post-hippie, pre-disco seventies New York City scene. But as loose and laid back as the record is, a smoky lounge act full of distortion and wah, it’s all in service of the era’s aesthetic—as carefully tailored as that maroon suit. We’re told it’s a personal record, so we believe it, but there’s not much to latch onto for proof. Instead, Daddy's Home seems to equate introspection with melancholy, or, worse still, monotony.

Songs run together one to the next, filling the air with a moody haze. Pay Your Way in Pain is a promising enough opener, almost a stylistic segue between Masseduction and Daddy's Home. With its heavy, fuzzy bass and gasping vocals, Clark pulls us back to the ‘70s by way of Bowie, Jagger, and Prince. But by track two, things get far more literal and stay there. Lest you forget that this record is influenced by New York, the call and response and dreamy sitar of Down and Out Downtown will remind you: “Bowery John/Forgotten, but not gone/Bodega roses in my hands.” (These bodega roses reappear later, too, on the closing track honoring Candy Darling.) Nods to the decade’s most emblematic artists start feeling like open-mouthed winks: Stevie Wonder synths and lyrics like “Hello on the dark side of the moon” on Melting of the Sun feel heavy-handed at best; Live in the Dream is little more than The Beatles’ Sun King or Pink Floyd’s Us and Them; literal Cassavetes heroines on The Laughing Man…hell, Sheena Easton’s Morning Train is the exact melody for My Baby Wants a Baby.

There are moments that shine here and there—an occasional riff or lyric that stand out from the rest. But on the whole it’s little more than set dressing, a movie sound stage with era-appropriate props. Any handling of her father’s release from prison feels clunky instead of confessional: “You still got it in your government green suit/And I look down and out in my fine Italian shoes/And we're tight as a Bible with the pages stuck like glue/Yeah, you did some time, well, I did some time, too.” It feels like rubbernecking, wanting more detail than what we already know from a tightlipped celebrity, but the promise was there and it’s normal to crave it. There’s nothing new here, knowing that Clark has achieved fame with her father behind bars. Nothing revealing about “sign[ing] autographs in the visitation room.” Any further reflection is oblique, brief, and quickly forgotten.

But there is one track that’s worth the price of admission on its own. Down is so emblematic of the new direction Clark has taken on Daddy's Home while still holding on to the frantic geometry of Masseduction. This is where we remember what she’s really capable of. It’s a time warp rather than a retread: the funk slap bass, the vintage groove. But it’s sexy and exciting in a way that’s missing from the rest of the album. Even while it dips a toe into the cliche with louche backing vocals and wah-wah pedal guitar solo interludes, each turn builds on the next with such flair that the drama is easily forgiven. Had the rest of the album capitalized on the breathless energy of this track, it would have been completely unstoppable.

To be successful, the conceit of a concept album can’t carry more weight than the craft. For all the insistence in interviews that she was able to let go on and eschew the angularity and impersonality of her previous releases, Clark has created an awfully restricted record. Weighed down by its own concept and bloated with references, there’s just no room left for emotional reckoning. In the end, we’re better off seeing Daddy's Home as purely an homage to the rich ‘70s funk and psychedelic music scene from somebody who only experienced it secondhand. It’s simply unable to withstand the added complexity of the personal narrative that we were promised.

27 June, 2021 - 20:06 — Gabbie Nirenburg