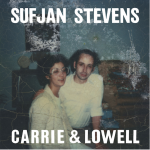

Sufjan Stevens Carrie & Lowell

(Asthmatic Kitty)

Sufjan Stevens has made a career out of imagining the lives of others through the eyes of a documentarian, examining regional history with a clarity of vision which provides a deep understanding of his nonfictional subjects. His ode to the states of Michigan and Illinois avoided a didactic purpose, depicting seemingly small lives rendered in grandiose orchestra leanings. In between this massive undertaking lay one of his most earnest statements, Seven Swans, which lay bare the spiritual core of humanity with theological observations applied with virtuous tolerance. The search of some kind of meaning is a recurring theme, and bears no relation to his musical pursuits - whether it’s a gently-strummed banjo or drawing mad sketches of heavily-layered electronic textures, the desire for some kind of connection, mortal or a higher being, becomes so irrepressible that it consumes all of his attention.

And yet, a passive tranquility spreads all over Stevens’s eternally boyish complexion. In maintaining an emotional distance he’s been able to focus everyone’s attention on all of his artful pursuits, and thus, the mystery of the man himself is relegated to a secondary plane. Which is surprising that Carrie and Lowell, his first proper release in over four years, is exclusively centered around his own personal distress. What once was a mannered, angelic voice, occasionally processed to glitched manipulation, is now reduced to a cracked whisper; eleven solemn confessionals performed with puncturing inflection in the intimacy of his own room. There are no exhaustive factoids surrounding his words, only plainspoken metaphors that offer shattering insight into the broken relationship he had with his estranged birth mother. Carrie, whom he never identifies by name, abandoned him when he was one year old, later to become a minor presence in his life. Stevens invites us to peer into a cathartic moment in his life without any trace of irony, bound by his faith, the geniality of his compositions often belying the grief that hides beneath the surface.

At first, he’s not quite ready to commit to the idea of speaking about his own personal strife with such stark openness. “And I don’t know where to begin”, he coos in album opener Death With Dignity, where he sees the necessity of reconnecting with his mother even though he accepts that it would’ve been impossible to make amends while she was alive. A fluttering pedal steel wavers as his awareness begins to work from inside, infusing a deep tranquility that brings to mind the hushed condemnation of Seven Swans. As with the majority of Swans, the album’s entire makeup is built around simple acoustic melodies, even though the occasional use of oscillating keys and minimal synth build-ups waltz against each other in harmony. One of the more skeletal compositions, All of Me Wants All of You, simmers with a calm tension, its bare autoharp vibrating steadily as he paints a faint memory of his young days living in Oregon before it leads us into a spellbinding outro.

I emphasize the ending to All of Me because the majority of Carrie and Lowell’s songs are self-contained suites in miniature. They’re all co-related to each other but not sequenced in tandem, and each provides its own finality as if representative of Steven’s personal divine order. These instrumental breaks in between songs are especially effective when they follow a moral imperative, like the devastating Drawn in the Blood, where Stevens feels unable to comprehend the circumstances surrounding him in spite of keeping strong ties to his faith. Stevens feels forsaken and filled with hopelessness, [“I’m drawn to the blood/the flight of a one-winged dove/How? How did this happen?] contemplating the unfeasibility of repairing his past mistakes seeing as even God himself is impotent to his own creation. Stevens has never sounded so defeated, though this repentance gives him continuance and growth in grace, and looks at it as an opportunity to find redemption in the aftermath of his own dissent.

The sincerity in Stevens’s voice is what elevates Carrie & Lowell from sermonizing drivel, who’s always maintained a considerable distance from his beliefs despite depicting Christianity in a very incisive manner. His internal monologue justifies a given level of intrusion, which he feels comfortable disclosing as a means to finally find some newfound starting point. The harrowing Fourth of July discards all that and simply puts the focus on his mother as she lies on her deathbed - a desolate piano glumly cedes to a number of affectionate terms, presumably told to him, though his marked indifference in this precise moment implies his open wounds are still in evidence. He declares with matter-of-fact callousness, “we’re all going to die”. The near absence of any kind of celebratory exuberance in the album is telling, though Stevens tries to implement a major scale on the title track, the closest it comes to an “all things go” hymn, where his tender fingerpicking and effervescent singing reflect a sound memory of his childhood even if the fickle presence of his mother remains.

Carrie & Lowell is as much about loss as it is about the passing of generations, and in Steven’s specific case, about the trials of maintaining a nuclear family in whatever way demands maturity. The attitude he expresses throughout is driven from an almost innocent angst, a chronological reflection of his suffering in different periods of his life that ultimately leads to a self-destructive, though necessary, downward spiral. This way of channeling feelings through song is what helps him gain perspective, that one can still find joy even during the ugliest of circumstances. There’s no closure as it reaches its end, only the acceptance that an ardent longing still burns his mind. "Search for things to extol/ friend, the fables delight," he asserts with some comfort in Blue Bucket of Gold, words that couldn’t better exemplify Stevens’s hunger for expression.

The storytelling in Carrie & Lowell is as vivid as its always been, only that the focus is his; he chooses to dismiss the small moments because he’s not preoccupied with them, and instead amplifies his grieving since he’s well-aware of what the bigger picture already holds. There’s nothing left to grasp, his faith is his stronghold. It was a chapter that needed to be told in order to move forward.

30 March, 2015 - 04:40 — Juan Edgardo Rodriguez