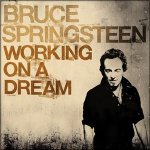

Bruce Springsteen Working On A Dream

(Sony)

Rare is the artist that can honestly say they're both recording and relevant after thirtysomething years - Kraftwerk managed it by dint of their return earlier this decade, while Neil Young and Lou Reed can both be arguably included on the list, but, so far, that's about it. Unless you count Bruce Springsteen, of course, and, really, why wouldn't you? In recent times he's become an indispensable critical touchstone thanks to the likes of The Hold Steady and The Delta Spirit (with even, lest we forget, The Killers paying lip service), he was responsible for the first album to really comment on the Bush administration (years before TV On The Radio did so to such striking effect), and he also happens to be the rock star most closely associated with, currently, the most famous politician in the world. Basically, he's never been so vital.

Frankly, given the groundswell of goodwill he's got to go on, it's perhaps unsurprising that Working On A Dream sometimes buckles under the weight of expectation, although it's also not too difficult to feel that the unusual haste with which it's been released has come at the expense of some of the, well, magic of more recent Bruce missives. For instance, there's little denying that bonus track The Wrestler is a rather lovely piece of work - its stirring opening even approaching Angelo Badalamenti territory - but its lyrical conceit is sufficiently sledgehammered for all its talk of one-trick ponies to border on the metatextual. The title track, meanwhile, pulls so fiercely on the lever marked "blue-collar manliness" that it narrowly overshoots archetypical Bruce awesomeness and ends up as stereotypical Springsteen-by-numbers, and Good Eye, while nodding unexpectedly at Beck with its penchant for mystical neo-blues, is similarly let down by a surfeit of throaty bravado that veers dangerously near self-parody.

Mind you, if the Boss himself is occasionally taking his eye off the ball, at least the same accusation can't be levelled at the E Street Band, who remain on compellingly imperial form throughout. Clarence Clemons' sax, in particular, is perfectly pitched to the chiefly positive tone the album seeks to strike, while Danny Federici, on his swansong with the band, steeps much of the work here in swathes of magnificent organ that'll appeal mightily to Springsteen acolytes. Moreover, there are a number of occasions when everyone involved is utterly at the top of their game; Tomorrow Never Knows has a heartening simplicity redolent of Jimmy Webb's finest endeavours, while there's a profound, hymnal quality to closer proper The Last Carnival, and, in fairness, it would be churlish to ask for a better opening gambit than Outlaw Pete, a restlessly shifting western epic that wouldn't sit uncomfortably on, of all things, any of Nick Cave's latter-day outings. Furthermore, Bruce hasn't made an album this in-love-with-love in years, and Queen Of The Supermarket finds more intimacy and romance on that location than any song since Billy Bragg's Brickbat.

It's that which is perhaps the most instructive comparison of all, as it goes. After all, its parent album William Bloke was released in the Tory twilight of 1996, when there was sufficient political optimism around for Bragg to flex his more personal songwriting muscles, and, given the similar air of hopefulness occurring transatlantically at present, Springsteen can likewise hardly be blamed for easing off on state-of-the-nation proclamations in favour of an album that, aforementioned bookends notwithstanding, settles for the upbeat instead. As an addition to a remarkable oeuvre, then, Working On A Dream has its worthwhile moments, but it's as a snapshot of a window of hope from an increasingly seasoned cultural commentator that it borders on the essential.

9 February, 2009 - 09:38 — Iain Moffat