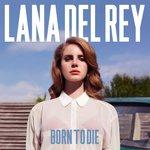

Lana Del Rey Born to Die

(Polydor)

The sudden rise of Lana Del Rey can only be attributed to each and every one of us. We’re just another cog in the enormous machinery of hype, wielding a little bit more force each and every day until it eventually takes a life of its own. But really, this advertising juggernaut isn’t any different to the one golden planogram marketers and executives have been practicing for years: look for a way to turn something conventional with a pinch of peculiarity, confound an audience by applying a fair amount of mystique and, ultimately, await the ending result after you’ve broadened an audience as much as possible. And, in reality, the reason why Lana Del Rey’s journey to prominence has been more pugnacious than the rest is because she posits herself with certain themes that are sacred to more assiduous music listeners.

Would she have received the same level of attention if she’d pranced around the stage like a euro-trash brat in neon tights and stiletto heels while some searing electro pop light show played in the background? Almost certainly, though her music would be burning the FM radio dial until the general public would eventually get tired of her all-too-obvious guise. Lana Del Rey was forcibly introduced to the world as a serious artist, a too-good-to-be-true, modern-day reincarnation of Nancy Sinatra for white, bespectacled music critics to gush over. The beginning to all this elaborate scheme was Video Games, a promotional cut featuring a droopy-eyed Del Rey sensually lip-syncing while presenting a series of juxtaposed, modern/classic arbitrary images that depict (to my understanding) how tabloid culture tampers one’s illusory attraction to fame and how nothing has changed; the same technique got carried over from her Kill Kill video in 2009, back when she was trying to make a name for herself without needing to resort to multiple wardrobe changes.

And as far as image goes, it seems as if her think tank of producers are still experimenting with her as it all rolls along – she started as an innocent, twinkling belle; then bore a cross, denim shorts, and a crown of flowers as if she were a New York barrio queen; and now straddles with an elegant attire like the finest of torch singers. The common consensus still thinks it reeks with artifice, similar to the same amount of snorting derision Madonna went through when she looked for inspiration in 30’s actress Dita Parlo in Erotica. And there are quite a few parallels between Del Rey and early nineties Madonna in Born to Die – a cold demeanor behind artificial boastfulness while making music that’s tender, approachable and, most importantly, distinctive under the typical pop fair of this time.

Del Rey never projects herself as audacious or courageous, which really hinders the possibility of ever taking Born to Die as a statement of defiant femininity. Right from the start, she doesn’t hold any punches and flat out pleas her man to walk on the wild side. She’s half-convincing, mainly since the succulent orchestral arrangement augments the lovers in peril motif more than the doing of her slothful, coarse voice. Which is not to say it doesn’t necessarily fit – just like in the dark ballad Blue Jeans, Del Rey sounds more comfortable when she tries to perform as a tough songstress. She does have a few tricks up her sleeve, like in Off to the Races, in which she modulates her voice from deep/talky and primly delicate to even the waggish, “boop boop de doop” pitch of Helen Kane in under two minutes time with striking effect.

The most curious aspect of Born to Die is how apropos its themes diffusely relate to the heavy scrutiny Del Rey is currently going through (but really, they’re just metaphors to prove she’s a worthy love interest) – not even they can stop me now/boy, I’ll be flying overhead/ their heavy words can’t bring me down, she sings in Radio, which diminishes the unvarying use of guitar twang to loosen up into a contemporary R & B production turned extravagant anthem. National Anthem is reprehensibly incoherent to a point that you’d think the songwriters didn’t even bother to do a rewrite – at first, a rapping Del Rey correlates proverbial wisdom like money is the anthem to success with the rich guy who will keep her alive, but most alarming is the how she’s acquiescent to the vanities of chauvinistic wealth of power (um, do you think you’ll buy me, lots of diamonds?); the cherry topping (yes, I also brought a gun) would be enough to make Honor Blackman roll her eyes. Where did the drive go, and why the submissiveness? She shouldn’t lose sight of this factual tidbit, either: don’t forget that money can easily buy success, too.

Besides the lush, opulent sounding hip hopera Carmen (no relation), the final stretch mostly resorts to the same ideas without that much needed oomph: there’s the militant drum pounds, embellished adornments (by way of funeral chimes or the passive motions of the cello), and the eerie, droning synth lines. It’s all sounds very immaculately polished, er, expensive. The same could be said about Del Rey herself, whose vocal output tries its hardest to overreach with the same amount of freedom as the ample resources she had to record Born to Die. And through it all, she credibly makes us see through her own lens, one that reflects an artist who’s so sure of herself she’ll bypass any critique brought upon her.

And who’s responsible? Well, the main culprit in her short-lived career continues to be us. There’s a really morbid quality to how the public feels so entitled to control her every move and mold her image to perfection. So why are we so enraged – is it because she became a phenomenon in the same way many of us would like to, by the same approachable methods and tools we’ve all been given instead of the bureaucratic methods of say, the support of a multi millionaire or an agent? Maybe so, but what we fail to understand is that she never really was one us from the start.