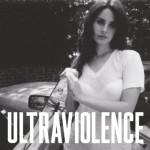

Lana Del Rey Ultraviolence

(Interscope)

It's a bit of a thankless job being a music critic; in fact, it can barely even be referred to as a "job" these days. However, once in a while, a great bit of writing will turn up that reminds you of why criticism is still important, a piece that elucidates the otherwise ineffable qualities that make a good record great, or take a poor effort to task in a fair, or at least a fun way.

And the response to Lana Del Rey's debut album was nothing of the sort. Instead what the record met with was a slew of self-importance that was, at best, pedantic, at worst, borderline misogynistic (not that the discussion about the socio-economic status of successful musicians isn't one that we should be having, but the fact that the conversation solely sprung up as a stick to beat an emerging female artist with, while scores of entitled white guys with guitars were getting off scot-free, did rankle somewhat). As it was, Born to Die was an interesting record, not without its flaws (namely slightly samey production and occasionally repetitive imagery) that met with a disproportionately hysterical reaction.

On the other hand, while the fairly sustained kicking she received can’t have been a particularly pleasant experience (as the recent unfortunate “I wish I was dead” brouhaha would suggest), it has allowed Del Rey to slip an awful lot of questionable stuff in under the radar. There was relatively little discussion of the sheer oddness of her live show, the fact that her increasingly concept-heavy videos were gradually getting longer and longer, and more and more overly serious, and, given how fashion's adoption of the Native American war bonnet has become something of a hot button issue, it’s interesting that del Rey wasn’t taking to task for donning one in her Ride video. Instead, having shouted her down before she’d barely even got her first words out, the angry hordes of the internet (and to an extent, the music press) merely shrugged their shoulders, having already prematurely shot their loads and said all that they needed to say, and much more on top of that.

Coming up to the release of that difficult second album, there was a sense that only something very bold was going to incite more than a slightly weary mild curiosity in response, and while some of the occasional spikes of interest were the result of fairly regrettable things (that “I wish I was dead” comment for a start), the most curious thing about Ultraviolence was an artistic decision; it’s hard to think of another out-and-out pop artist who would turn to The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach to handle production duties on that record. After all, hadn’t we all learned that unfortunate Alicia Keys and Jack White-related event? And even more perversely, the record was announced with first single West Coast. Its hazy and woozy yearning might be the perfect audio distillation of a summer romance, but there was almost something downright uncanny about a big pop track that saw what everyone else was doing and went about doing the opposite, slowing down where everyone else was speeding up, sounding a bit like riding a seaside amusement park’s knackered old carousel while slightly drunk.

That pretty much sums up Ultraviolence’s appeal; it’s a record that does an awful lot of things ‘wrong’ and is all the more beguiling for it. The title track, and probable high point, for instance weirdly borrows its intro from Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’ Assassination of Jesse James score (which is no bad thing at all, even if the general lack of discussion of this suggests that it’s merely a completely unintentional coincidence), throws in a very blatant reference to perhaps the most brilliant, and troubling, moment in the Phil Spector back catalogue, applies the sort of forced cool, and not entirely convincing bad girl role play and character adoption that pretty much everyone gets over in their teenage years (it's very hard to believe that anyone's ever seriously been given the nicknames 'Poison' or ' DN, that stood for Deadly Nightshade'), and throws in some faintly fishy glamorisation of violence (which to be fair we can’t say de Rely didn’t warn us about, what with it being right there in the album's title), yet comes out as something quite devastating, where the heightened pitch, and heightened stakes of her pleading to go 'back to New York' feel entirely real.

Which is largely down to technique, after all, the instant scrutiny that Del Rey found herself on the receiving end of after her first single (under that name at least), hasn't really left her much time to develop; the same images of bad boys and red dresses reoccur here. What she has been able to work on however, through all those slightly shaky live shows, is her voice, which started out as a pretty drawl, full of studied boredom, and now stretches to a slightly deeper drawl on one hand, slightly Cher-like in its croakiness, to an almost angelic like soprano.

As for the lyrics being delivered; some are more successful than others. Lizzie Grant’s roleplaying as Del Rey might be something that has been discussed ad nauseam, but in reality Del Rey isn’t a character, but several. Each might be linked by their sharing similarly sketchy social circles and taste in men, some, however, rise above the invocations of tragic Hollywood beauty. Brooklyn Baby’s aloof protagonist feels very real in her unrepentant annoyingness, although whether the portrait is meant as a condemnation or a celebration is a tricky question, as the song itself refuses to judge, partially because of Del Rey’s aforementioned blank delivery, partially because of the role seemingly tying in to her generally accepted persona as an overly entitled East Coast girl. And further intentional fun is had with her persona on the eye-wateringly titled, Fucked My Way Up to the Top, which thankfully doesn’t welch on that initial promise and fully lives up to its diva-potential.

Similarly, Ultraviolence’s musical content displays an equal sense of sharpness, demonstrating that Del Rey has been learning from the past. She might be kicking somewhat against the EDM dalliance on Summertime Sadness that actually launched her as a genuinely successful pop artist, in releasing a slow, guitar-based record (which is a pretty wise idea to avoid being pigeonholed for good), but there are also moments where previous successful ideas are fleshed out further; the rich horn section that was added to her sound on Woodkid’s remix of her debut’s title track makes its reappearance on Sad Girl. It’s enough to make you wish that she’d hook up with the Grimethorpe Colliery Band for album number three.

Other self-referential moments occur here and there on Ultraviolence – the string section from National Anthem makes a reappearance on Old Money, and, as if the title track wasn’t unsettling enough, the “Lay me down tonight” refrain from Fucked My Way Up to the Top hovers eerily over the song’s climax - just buried in the mix so as not to bash the listener over the head, but rather to reward close attention with the suggestion of a sense of continuity. It’s debatable whether the story really adds up to anything much - particularly with the notion that we’re not always dealing with the same character in Del Rey’s work – but, it’s interesting to come across such concerted efforts at myth-making. And the references to other aspects of pop culture, which could easily have been written off as a lack of original ideas, serve as a clarification point; that Del Rey might be a ‘manufactured’ artist, but not in the commonly understood industrial sense, rather as the result of an intense, thoughtful consumption and curation of pop culture on her part. It might not exactly be Del Rey/Grant’s ‘personal’ story, but it’s a story that’s personal in the sense that it comes very much from her interests. Even the uncomfortable glamorisation of sexual violence is really just her finally living up to her repeatedly admitted admiration for David Lynch, as does the reverb-heavy production and distant guitar twangs of Pretty When I Cry (who would have thought that Chris Isaak would have been ultimately responsible for one of the more fashionable sounds in pop music in 2014?.)

To an extent, this reappropriation is also where Ultraviolence ultimately comes unstuck; in that her attempt to completely abandon current pop tropes and fully channel that old-school showbiz glamour on a cover of a minor-work by the R&B songwriter Jessie Mae Robinson, The Other Woman ends the album on something of a damp note; it’s perfectly pleasant, but at best even at the time of original composition it would only have ever been a bit of filler; and not really apt material for a major pop album’s grand finale. While it would be tempting to pretend that the album instead climaxes with the rather more striking Black Beauty, as after all, what do “Deluxe Editions” and “bonus tracks” even mean anymore, considering that track would also mean dragging the unfortunately Red Hot Chili Peppers-esque Florida Kilos, and the incredibly ghastly mock-cock-rock of Guns and Roses, into the discussion too. But still, underwhelming ending aside, it’s fair to say that Del Rey (and her collaborators) have more than risen to the challenge of keeping her a part of the pop culture conversation, for all the right reasons.

4 August, 2014 - 04:19 — Mark Davison