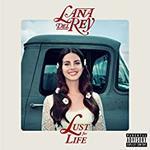

Lana Del Rey Lust For Life

(Polydor / Interscope)

To say I have a personal stake in Lana Del Rey's activity as an artist is an aggressive understatement. Lana's music has fueled my slumbers, workouts, shower concerts and friendships. Honeymoon is the album I listen to on international flights when the fear of tumbling into the Bermuda triangle paralyzes my ability to reason. Ultraviolence was the soundtrack to an electric summer in Boston. Paradise and Born to Die accompanied dismal high school hallway shuffles and awkward forays into hipsterdom. All of this is to say that I want Lust For Life to be the quintessential LDR album, the one in which she melds her hip hop fetish with her Lolita complex with her classic rock roots, all without sounding ridiculous.

Lust For Life does just that. But it also sounds ridiculous. I was halfway through a walk while listening to the record when I realized that "wide mouth tang" and "Weimar stain" was actually "white Mustang." Admittedly, it's nothing new for Lana. She's purred and slurred her way through gauzy film noir numbers and pop standards on previous albums like a sozzled Golden Age starlet. It's a pleasure to decode the lyrics if they're like the ones in Heroin ("Life rocked me like Motley / Grabbed me by the ribbons in my hair"). Other times it's a letdown, as is the case with the self-absorbed redux of High by the Beach titled 13 Beaches: "It took me 13 beaches to find one empty / But finally it's mine." Of all the topics to address on her fifth album, the privacy woes of a jaded popstar aren't really stimulating or interesting, and neither is her love interest's white mustang.

In all fairness, this is the singer who brought us a song called Fucked My Way Up To The Top. Lana has always wielded ridiculous lyrics with an ironic edge so sharp it could cut the leg off an elephant. When she rhymes "girls" with "pearls" and "curls" in When The World Was At War We Kept Dancing, it's an assertion of idiosyncrasy, a reclamation of a classic rhyming pattern that all "serious" artists would avoid. Besides entertaining a healthy sense of irony, Lana also plunges listeners headfirst into the sonics of drama: overblown orchestration, scooped vowels and cinematic production values. All of which often results in her music being labelled as cringe-worthy and pretentious, two adjectives which critics have been lobbing at Lana's head since her debut.

Here's a thought, however: what if we allowed female musicians to write bad lyrics? What if we gave their experiments the benefit of the doubt the same way we fawn over Kanye's twisted brilliance or Radiohead's disturbed opuses? Some songs just don't work—that much is true with any artist. But Lana's been weaving her albums like tapestries, savoring recurrent images and themes in a way that deserves serious consideration. She obsesses over sweet, rich sensory delights: diet mountain dew, cola, soft ice cream. In Old Money, a deep cut from 2014's Ultraviolence, she crooned about blue hydrangeas and cashmere. She likes cocaine, criminal old men and America.

So much of Lana's music derives meaning from the mere mention and connotative power of these topics. While she never really has much to say beyond the fact that she likes them, her insistence on writing about them merits attention. Usually, she hints at her intentions through her song titles. Cherry, for example, is a standout track, an ode to the alternating sweetness and bitterness of romance. Feeling no particular need to make sense, she moans tunefully: "Darlin' I fall to pieces when I'm with you / I fall to pieces / My cherries and wine, rosemary and thyme. And all of my peaches are ruined." In the background, the words "bitch" and "fuck" swirl like angry afterthoughts, while trap drums and rippling strings punctuate her melancholic vocals. Later on in Heroin, she reminisces about the toxic allure of cities, people and substances that keep her hooked ("I want to leave / I'll probably stay another year"). Pay attention and you'll hear her substitute heroin for marzipan in the final iteration of the chorus.

The second half of the album sees her lengthening her song titles and shifting her lyrical approach away from sensory images. While neither Summer Bummer or Groupie Love break new ground lyrically, her collabs with A$AP Rocky manage to be funky and cynical at the same time, and the synergy between the two artists is palpable. She waves her ex's cigarette smoke away in In My Feelings, and it's nice to see her disdaining a dysfunctional man for once, instead of glamorizing him. Coachella - Woodstock In My Mind is an instant classic with an unfortunate placement amid the horse latitudes of the record. Her elegant duet with Stevie Nicks only sounds better with each listen, as does Tomorrow Never Comes, where Sean Lennon marries his acoustic guitar melodies with Lana's sweeping reverbs.

To be clear, I have no idea what this album purports to be about. The scope of Lana's interests begins with the generational on the excellent first single Love; shrinks to the personal in songs such as 13 Beaches, White Mustang, and In My Feelings; expands to the national with eye-roll-inducing God Bless America - And All The Beautiful Women In It; then transcends the material with a series of abstract reflections on the problems of beautiful people, the prospect of war, and the promise of living a meaningful life. Overall, Lana's philosophical insights don't yield very effective slogans: "Change is a powerful thing/ people are powerful beings," she chants in the pretty but toothless Change. But now that she's got a stage and an audience, one gets the sense that she'd rather sing about simple pleasures and fundamental truths. This is her deal, the crux of her ethos, that it's okay to be young and in love, even if she spends her youth snorting lines, squandering her love and singing the blues. Lust For Life may be a scattered, confusing record, but it's a beautiful ride—one worth repeated listens, even if Lana's intentions—like her enunciation—aren't always clear.